- Home

- Barron, Laird

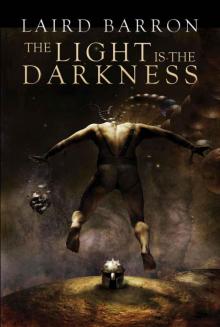

The Light is the Darkness

The Light is the Darkness Read online

FIRST DIGITAL EDITION

The Light is the Darkness © 2012, 2011 by Laird Barron

Artwork & Illustration © 2012, 2011 by David Ho

All Rights Reserved.

This edition published by:

DarkFuse (In association with Arcane Wisdom)

P. O. Box 338

North Webster, IN 46555

www.darkfuse.com

Copy Editing by Leigh Haig

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the author.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Larry Roberts, the Roberts family, and the magnificent artist David Ho.

More thanks to my friends Jody, John L., Paul, Steve, Norm, Scott N., Nick K., Wilum, JD, Chesya, Justin, Ellen, Gordon, Lucius, Jeff F., Jeff V., and my brother Jason. And of course, thank you to my fans, without whom I’d have nothing.

This one is for my stalwart companions Athena, Horatio, Persephone, and Ulysses who stood by me through a long, dark winter.

It’s also for Erin, in spite of, because of, everything.

Chapter One

I

After Conrad followed yet another dead end sighting of Imogene, he’d exhausted most of his cash and all his favors. His sister’s trail of bloody breadcrumbs vanished into a South American rainforest. Imogene, a crackerjack FBI special agent, had originally disappeared in Mexico several years beforehand while hunting Dr. Drake, the fellow who may or may not have murdered their older brother Ezra.

That most authorities took Drake’s decade long absence as proof of death (he’d been older than the oldest Nazi war criminals last anyone saw him in public), hadn’t dissuaded Imogene from her mission of vengeance. She’d believed the doctor possessed great and diabolical secrets, an unnatural lifespan being least among these.

Brother dead, suspect missing, sister missing too. Gears within gears, wheels within wheels, irony piled upon irony. Lately, Conrad wasn’t sure whether he was chasing Imogene or her ghost.

The only good thing to come from months spent chopping through the jungle between backwater villages was the discovery of yet another in a sequence of cached papers and films Imogene periodically dropped for him like clues in a bizarre game of cat and mouse. These latest papers were left tucked inside a firebombed bunker and revealed her recent contact with another family acquaintance he’d long thought dead or relocated beyond the reach of friend and foe alike: Pablo Souza, known internationally as the Brazilian, a chemist and surgeon of some infamy and a former henchman of Dr. Drake.

Rumor had it, and a hasty note among the top secret military documents she’d stolen confirmed, Imogene had sought Souza out to purchase a serum the old man perfected, an elixir that contained most wondrous and potentially lethal properties—One drop will grant you immortality unless it strikes you stone dead! The alleged properties were so wondrous they’d attained the stature of legend.

Imogene’s note read in part: I know where Drake is hiding. Problem is, you can’t get there from here. Souza gave us a way in, though. The kicker is, Souza’s little wonder drug isn’t what made Dr. D. an ageless villain. Turns out it’s the other way around. But, daylight is burning and I have to make tracks. So, this is it, brother of mine. I’m gonna eat the worm and shed this skin. Raul is coming with. Final showdown on eleven at eleven. Don’t try to follow us. Love you, kiddo. The Raul she mentioned was Raul Lorca, a decorated Mexican scientist and Imogene’s lover of several years. Her loyal sidekick. Mexican intelligence had a few questions for him too.

Unfortunately, Imogene was long, long gone and the Brazilian skipped the country just ahead of Conrad’s arrival, although as more than one law enforcement agency wanted Souza’s head on a pole for various crimes against humanity dating back to the Second Great War, his latest absence might’ve been a coincidence. The old boy tended to move frequently. As for Souza’s miracle elixir: those in the know scoffed and dismissed the existence of the drug as a fairytale, mythical as Ponce de Leone’s fountain. Conrad didn’t care about the skeptics. Good enough for Imogene was good enough for him, and either way, Souza was another link in the chain that would help him locate his sister for a homecoming or a funeral.

Conrad put out the word he was now looking for the Brazilian in addition to Imogene and her lover. Tracking the chemist would be expensive, if not impossible. Luckily, Conrad’s membership in the Pageant, while exceedingly hazardous, rewarded him well. He made the call to his patron, a reclusive industrialist named Cyrano Kosokian, and scheduled a ludus with a top ranked contender. They would fight that coming spring in a crater in the desert. The terms were particularly brutal—a blood match unto dismemberment or death—and thus the payout extravagant. Sufficiently lucrative, he hoped, to ameliorate the massive debts he was in the midst of accruing in search of Imogene. Then he chartered a flight to a remote Polynesian island resort and dropped off the map for a while.

He thought of it as returning to the nest.

The resort was contained within the shell of a ruined castle on a hill above a white beach. It loomed over a jetty, a handful of antiquated fishing boats, and farther out, at the mouth of the harbor, a reef. During the winter season the resort was deserted but for a skeleton staff and a handful of fellow eccentrics.

Conrad practically owned the place. The resort was scarcely upscale, being rather an ancient church converted to a fortification against buccaneers, and, during one of the government’s more prosperous and ambitious eras, remodeled as a hotel casino meant to attract the big fish: filthy rich Americans and Euro nobility seeking anonymous escape from the paparazzi. The dingy façade, weedy courtyard, two hundred year old clay tiles that let in the rain, the moss and the cracked plaster, yellow as decayed ivory, the sullen employees, and the occasional cockroach, combined and collaborated to lend the villa an aura of Third World charm.

The owners were proud of their erstwhile clientele. Dim photographs of decrepit Hollywood celebrities, Vegas singers, 1980s supermodels, and a famous Latin dictator, glinted in the lobby, the dining room and the lounge. The stars grinned and grimaced, were mainly ghosts, unknown to the bartenders and the boys who carefully swept the floors.

In the mornings while the sky was yet dark, Conrad dressed in the rubber suit with its leaden patches and weights at wrists, waist and ankles, and ran along the beach until he came to the mountain path and followed it up and up above the tree line, across the black shale slopes and gaspingly at last until he fell to his knees in the shadow of the caldera of a dead volcano.

Come the tourist season the mountainside would be strewn with panting men in flowery shirts and sunburned women in floppy-brim hats and starlet sunglasses the natives sold by the gross alongside key chains, pottery and bananas at the little thatch stands on every other corner. But this was winter and the mountain was peaceful as westerly light began to bleed across the ocean. Conrad sprawled among the small stones and powdered ash and when his air returned, lurched to his feet and plunged back down toward the trees and the beach that slashed like a white scar.

The staff, a cadre of dark, pinch-mouthed men in secondhand tuxedos, lugged a buffet bar into the courtyard. There he collapsed beneath a faded parasol and gorged on slabs of boar and goat, bread and cheese, and gallons of goat’s milk while a servant in a dirty white jacket waited at his elbow to pour his coffee and light his cigarettes. The cigarettes were killing him, he knew. Gravity was killing him, and diffidence too, and someone, somewhere was waiting to kill him if these things failed. In contemplation, he’d have another smoke.

Conrad always slept for several hours. Later, in the early afternoon of even-numbered days, he went to a section of the beach where

old rockslides had deposited boulders among the shade of the palms, and lifted the smallest of these rocks in his arms and lumbered to the surf and tossed them into the bay. He persisted mechanically until a trench gouged the sand and the skin on his arms glistened slick with blood and he could no longer grasp the boulders, could scarcely stand.

Odd days he swam from the jetty through the shallow harbor past the breakers until the water cooled and darkened beneath his threshing limbs. On the way home he pushed harder, harder, put the hammer down and drove balls out, held nothing in reserve. Occasionally, his body became lead and he sank in the greenish lagoon near the shore, plunged like a statue, trailing his life-breath in a streamer of oblong bubbles, sank toward the hermit crabs and the coral and algae scabbed rocks. Three of the more reliable natives, the ones he reckoned with the least hatred toward white men and Americans in particular, who were paid quite handsomely to sit and observe these solitary excursions, eventually set aside their shared flask of coconut rum, clamped hand-rolled cigarettes in their teeth and poled a skiff alongside and hooked Conrad’s limp bulk with gaffs. They towed him to the docks where two more fishermen waited to roll him onto his face until the water ran from his lungs and he coughed his way back among the living. Slowly, laboriously, as Conrad weighed something on the scale of a small walrus, they loaded him into a cart and pushed him up the hill and to his quarters for another long nap.

Upon emerging, torpid and semi-feral, he’d feast again and gulp prodigious quantities of local wine from earthen jugs. Strange, leering visages were carved into the jugs. Conrad had seen many of these in various forms stacked on the hotel’s storeroom shelves, the rude pantries of the shacks and shanties—always well hidden from the casual inspection of the rapacious tourists and their cameras and video recorders. The concierge, a smooth, walnut fellow named Ricardo, because his mother originally emigrated from Madrid where she’d been an actress of minor accomplishment, informed Conrad that an old family of master potters made the jugs. The jugs were good for trapping the power of spirits if one knew the proper incantations. The family was scattered across the islands and had faded into obscurity around the time most of the population converted to Christianity. Old ways never really died and the spirit jugs gradually reappeared during the empty winter months along with the traditional fertility charms and clay idols of elephantine creatures squatting upon thrones of skulls, and shark-headed humanoids whose faces were obliterated by the slow burn of centuries. Effigies of dark gods, the concierge said. Makers and destroyers according to their whims.

Conrad awakened occasionally to flickering orange shadows upon the ceiling; sing-song chants, the strident melody of reed pipes, the rhythmic kathud of drums. From his balcony he watched the sinuous roil and flare of bonfires among the monoliths embedded in the black line of foothills. After a time he returned to bed, sometimes dreaming of men in masks and headdresses assembled in the hotel lobby, their eyes turned upward and boring through the floor of his room. Spearheads sparked and glinted in the dimness; machetes clinked and scraped against wooden harnesses of war.

The weeks lay before and behind him, an endless white waste.

No matter the day, as dusk began to press the sun against the waves, Conrad dragged a wagon to a cane field behind the resort. He’d unload his weapons and get down to business. The light work first—he flung a brace of javelins into sacks of straw tied to rickety bamboo cross posts; first right-handed, then left, mostly at close range, but sometimes as distant as one hundred paces, which was too far to be considered effective as a general rule; and after the javelins came the sling and he hurled smooth, gray river stones and watched straw puff as from bullet holes and he continued until his shoulders ached.

By then, night fastened upon the land. Fortunately, there on the coast the starry sky hung within a hand-span of the earth it was never truly dark. He’d practice with the heavy weapons: chains, mauls, the Visigoth axes, the great iron mace from Mongolia with its iron head and flanges that shrieked as he swung at the bamboo thickets and splintered the smaller trees, made vees of them like a swath of broken toothpicks; and as he chopped, his feet moved in the katas of feudal samurai, side to side and diagonal; and older steps, the berserker rush of the Vikings and the Gauls. He ravaged through the copses in brief charges of the Roman cohorts and the implacable Spartans, until, at last it was done and the steam rolled from him in clouds.

After supper he broiled in the sauna and then off to his suite to brood over a collection of cryptic papers assembled from the dusty shelves and trunks of antiquarian bibliophiles from Alaska to Katmandu, or set up the antique projector and meditate upon the kaleidoscopic horror show spun from a film reel he’d found among his long lost sister’s effects, all the while repeating one of several mnemonic triggers that would alter his brainwaves and open a door to elsewhere, wherever that might be. From the glimpses of bloody bones and colloidal darkness, he wondered if it might not be Hell itself.

He doggedly awaited some sign of apprehended knowledge, a stirring of the atavistic consciousness. Occasionally, shadows and mist coalesced into nightmares of massive tendrils uncoiling from a vast and dreamless void, and visions of antlers and fiery destruction, but none of it made sense except that now, if he concentrated to the point of a violent migraine, he could cause a spoon to vibrate in a bowl by will alone and possibly once he had slightly levitated a few inches above the blanket while in lotus, but he had been drunk, so very drunk.

Such was the daily ritual.

The morning the neurologist landed for a series of scheduled tests, Conrad was on the lounge terrace, sipping the blackest of black coffee and smoking cigarettes. A radical chief of staff at a mainland university paid exorbitant fees for the privilege of monitoring Conrad’s unusual brainwaves.

Rains had begun the previous evening. Lightning stabbed at the horizon. A small man in an overcoat exited the plane and one of the attendants held an umbrella for him as they hurriedly made for the hotel. This was Dr. Enn, one of several persons Conrad had contacted to conduct periodic tests of his neurological activity. Soon came a number of trunks and cases, dutifully unloaded by hotel employees and wheeled up the dock on hand trucks.

Two more visitors, heavies in suits and glasses, trailed. The short, thick fellow with the bad 1970s haircut was Agent Marsh. The suave, dark gentleman who looked like he’d strolled off the cover of GQ was Agent Singh. Both worked for American intelligence—the National Security Agency. Conrad suspected he would have to kill them sooner or later. For now it meant he would have to relinquish the papers and film he’d retrieved in Brazil. Simply no time to stash everything. So be it: he’d hand over his curiosities like a good boy and maybe get the operatives to do some digging on his behalf in the bargain.

He finished his cigarette. The island and its routines were the nest. Now he’d crawl back into the egg.

II

He lay suspended beneath miles and miles of blue-black ice and dreamed.

This ice was the oldest kind that had come down from the great outer darkness and closed around the world eons past. Trapped in its glacial folds was a cornucopia of geological oddities: Cryptozoic bacteria writ large, fossilized palm fronds of ages when blood-warm oceans and perpetual fog wrapped hemisphere to hemisphere; insects, animals, men, and things that resembled men, but were not, and vast globular superstructures of primordial jelly and miles-long belts of ganglia, all caught fast in glacial webs, all preserved and on exhibit in the gelid recesses of his dreaming brain.

Conrad dreamed of waking, of thawing, which was a reliable indicator that control was shifting his way, that he had swum up from the Hadal depths to a semi-lucid state, and so he blinked away the ice and whispered the Second Word, which was leviathan, and was again a child in the backseat of Dad’s car. They were in Alaska, hauling ass along the Parks Highway, bound for Anchorage and the airport. A DC-10 waited to transport them to Spain and the clinic where miracles happened.

Mom and Imogene were somewhere ahead,

cutting through arctic twilight in a Citroen with bald tires and a broken heater. Mom was reckless at the wheel, a damn the torpedoes, cry havoc! kind of lady and likely she was puffing a Pall Mall and lecturing hapless Imogene on the essential instability of subatomic matter. Or how the headhunters in Papua, New Guinea performed fertility rituals with the skulls of their victims.

The windows were frosted over, but when Conrad scratched a circle there was Denali rearing in the middle distance, a chunk of red-black rock wearing a frozen halo.

His head ached. It ached all the time those days; ached as if it were he and not brother Ezra being eaten alive by a melanoma the diameter of a mango. Ezra rode shotgun, the metal nub at the crown of his Seattle Mariners baseball hat chattering against the glass. Ezra was the elder; a little league all star shortstop, future hall-of-famer and devoted tormentor of younger siblings, currently under the weather and fading fast. Ezra wasn’t much for trapping groundballs or distributing Indian burns these days; he’d withered to skeletal dimensions that Conrad could tuck under one arm.

1980.

This was the year the famous Japanese mountaineer Kojima bought a one-way ticket to visit his ancestors. Kojima wasn’t dead yet either; he still had a few hours to watch his extremities freeze, to ponder whatever great men ponder as they wait for the curtain to drop. Kojima had been in the news all week. As they toiled past the shadow of his tomb, Conrad gazed at the storm clouds and tried to touch Kojima’s thoughts.

When he asked Dad his opinion, Dad grunted and said mountain climbers were responsible for polluting the wilderness with discarded oxygen bottles and food wrappers, that they were possibly the filthiest creatures alive.

The Light is the Darkness

The Light is the Darkness